Caterina Assandra

Famous Italian organist, composer and Benedictine nun, Caterina Assandra, whose motets were among the first of the Roman style to be published in Milan, was born into an affluent family, likely in Pavia. Assandra’s musical education began in her childhood when she studied with private tutors hired by her father. Living in a time when music making was judiciously monitored, Assandra’s musical education was justified as serving a religious purpose.

Assandra took her vows as a nun in 1609 at the cloister of Sant' Agata in Lomello near Pavia. While at the cloister, Assandra studied counterpoint with Benedetto Re, or “Reggio,” one of the leading teachers at Pavia Cathedral. She called him “Maestro di contraponto,” based upon her notes in Motetti à due e tre voci, Op. 2 (Milan, 1609), which was dedicated to G.B. Biglia, the Bishop of Pavia. The publication includes ten works for soprano and bass voices and features two of Re’s compositions. In response, Re later published works of Assandra’s along with his own music.

Assandra’s compositional style was influenced by local composer Agostino Agazzari. She composed in both traditional and reformed styles, showing progressive tendencies, and her setting of Duo seraphim may have inspired Monteverdi's setting of the same text (Both videos linked here). Her compositions were largely published between 1609 and 1616, and it is assumed that her duties as a nun took over after that point, which halted her composing career. Two of her motets were later re-published in German anthologies and, unlike many other nuns who wrote music at that time, her work was known beyond the boundaries of her home country.

(https://www.amodernreveal.com/caterina-assandra)

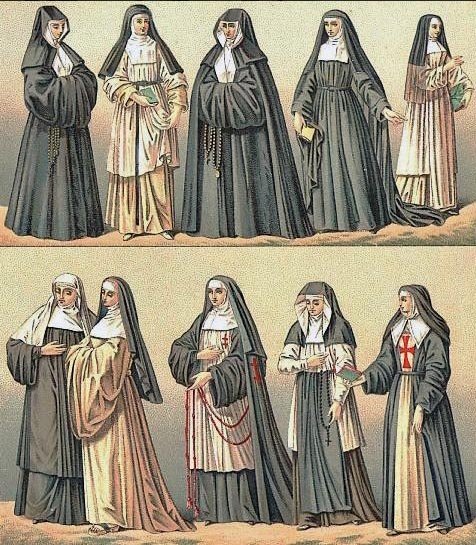

Because convents were typically under the control of clergymen, the local population’s permission of musical activity often determined whether or not a convent actually allowed its nuns to perform. Convent music was not intended to be public, and the strict enforcement of clausura, which restricted nun’s access to the outside world, made it difficult for nuns to be seen and heard beyond the walls of their convents. This increased the perception that they were celestial and heavenly beings, which aided the church in maintaining its mysterious image.

Several composers of convent music, determined to associate with the outside world and ensure their music was proliferated, defied the rules of clausura. Their fortitude provides us with the opportunity to learn about these composers and their work, while gaining a greater appreciation for sacred and secular compositions beginning in 16th century Italy, paving the way for future generations of women composers and musicians to perform, write and disseminate music.

(A Modern Reveal)

The Convent: The Women Making Music During The Renaissance

In Renaissance Italy, one of the only ways for women to pursue their musical inclinations was to become nuns. Insulated convent communities provided women the opportunity to compose and perform music, a practice that would not have been condoned outside convent walls. (A Modern Reveal)

Convents fulfilled many functions in medieval and Renaissance societies: they were the economic and spiritual heart of many communities, safe spaces for women at all stages of life and from all strata of society, and often places where women could thrive intellectually, practically, and creatively away from the intense scrutiny of male relatives. Women trained in music were particularly welcomed, because fine music could elevate a house’s reputation, which could then attract wealthy families to the convent to celebrate weddings and burials, and to provide the more permanent investment of daughters as novices. But even more importantly, the nuns’ primary purpose was the Opus Dei, the recitation of all 150 biblical psalms over the course of the week; through this musical labour, they ensured the spiritual wellbeing of the entire city. (Musica Secreta)

Convents were managed in a very business-like manner, almost like modern theatre companies. “Convents competed for musically-able young women, and mother superiors had talent scouts searching for young women who might be poor but talented. I found a letter written to the abbess at Le Murate in Florence where a woman is saying: I have this young girl in my household, she has 'venti voci', twenty notes – the gamut is supposed to be twenty-two notes, so she has this huge range – and a 'good bass'. This girl wouldn’t have brought financial benefit to the convent but she was going to be a very useful singer with those low notes,” says Stras. “There is also a record of a conversa, a servant nun, who was so musically able that her convent petitioned the Pope to have her elevated to the status of choir nun, and the Duchess of Urbino, Lucrezia d’Este, paid her dowry so that she could be added to the convent’s musical ensemble.” (Bach Track)

More Assandra

Maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.